Cottage on Fire, Bekonscot

Cottage on Fire, Bekonscot

Monday, 9 November 2009

Buildings of Disaster

Constantin Boym

Laurene Leon Boym

design year:

1998

manufacturer:

Boym Design Studio, USA

materials:

bonded nickel

notes:

Souvenirs of human tragedy, even violent events, are a part of our object-history. Each year hoards of people visit the battlefield of Gettysburg and the site of the car crash which killed Diana, Princess of Wales. Perhaps we embrace horror so that we may contain it, even feel some sense of control over it.

Buildings of Disaster is a project begun by Boym Design Studio in 1998. This thoughtful project is described by the creative director, Constantin Boym:

"The end of a century has always been a special moment in human history. While we no longer expect the world to come to an end, we all still share a particular mood of introspection, a desire to look back and to draw comparisons, and a sense of closure and faint hope. Above all, the end of the century is about memory. We think that souvenirs are important cultural objects which can store and communicate memories, emotions and desires. Buildings of Disaster are miniature replicas of famous structures where some tragic or terrible events happened to take place. Some of these buildings may have been prized architectural landmarks, others, non-descript, anonymous structures. But disaster changes everything. The images of burning or exploded buildings make a different, populist history of architecture, one based on emotional involvement rather than on scholarly appreciation. In our media-saturated time, the world disasters stand as people's measure of history, and the sites of tragic events often become involuntary tourist destinations."

Monday, 2 November 2009

Thursday, 8 October 2009

Wednesday, 7 October 2009

Friday, 2 October 2009

Things to Do and See 2

Victoria Miro Gallery

16 Wharf Road London N1 7RW t: 44 (0)20 7336 8109 Tuesday - Saturday 10.00am - 6.00pm Monday by appointmentThursday, 1 October 2009

Things To Do and See 1

Just How Strange Are Modern Materials? PIG 05049

PIG 05049

"Christien Meindertsma has spent three years researching all the products made from a single pig. Amongst some of the more unexpected results were: Ammunition, medicine, photo paper, heart valves, brakes, chewing gum, porcelain, cosmetics, cigarettes, conditioner and even bio diesel.

Meindertsma makes the subject more approachable by reducing everything to the scale of one animal. After it's death, Pig number 05049 was shipped in parts throughout the world. Some products remain close to their original form and function while others diverge dramatically. In an almost surgical way a pig is dissected in the pages of the book - resulting in a startling photo book where all the products are shown at their true scale (1:1)."

Nothing Can Be True Which Is Not Beautiful

The industrial revolution fundamentally re-shaped the organisation and mechanisms of society. Karl Marx describes for example that the division of labour creates what he calls 'alienation'

Equally, we see a kind of alienation from materials themselves.

This is expressed by John Ruskin – who if Nikolaus Pevsner is to be believed - is the origin of the morality of Modernism.

Here are a few Ruskin quotes to give you a flavour of his attitude:

"Every increased possession loads us with new weariness."

"There is scarcely anything in the world that some man cannot make a little worse, and sell a little more cheaply. The person who buys on price alone is this man's lawful prey."

"It is his restraint that is honorable to a person, not their liberty."

"It is far more difficult to be simple than to be complicated; far more difficult to sacrifice skill and easy execution in the proper place, than to expand both indiscriminately."

"He who can take no great interest in what is small will take false interest in what is great."

And especially relevant to us:

"Nothing can be beautiful which is not true."

Ruskin was describing a form of alienation from what me might call a 'natural' state caused by industrialization.

For Modernism, the idea of 'truth to materials' was fundamental - that any material should be used where it is most appropriate and its nature should not be hidden. Concrete, therefore, should not be painted and the means of its construction should be celebrated.

But honesty is hard, and if you look closely, you find that much of the 'truth' of Modernism was actually a clever disguise. That Mies' I-sections are applied decoration rather than structural. That the Villa Savoye is rendered brick, rather than concrete.

We might speculate that this demonstrates the impossibility of a singular truth – that it is impossible to manifest (especially in architecture, where costs, project managers, clients and contractors will conspire against such embedded ideology). Instead, what is important is the idea of a truth. And that you might have to lie to make your truth real. And of course, that there are many truths. Each of these truths reflects a particular position, particular view, and particular ideology.

For us, at the other end of the industrial revolution, materials have become something else. And so has 'truth'.

We might look to more contemporary sources to understand our relationship – and to chart our alienation – from materials.

We might think of Warhol's Brillo Boxes, which are representations of cardboard boxes.

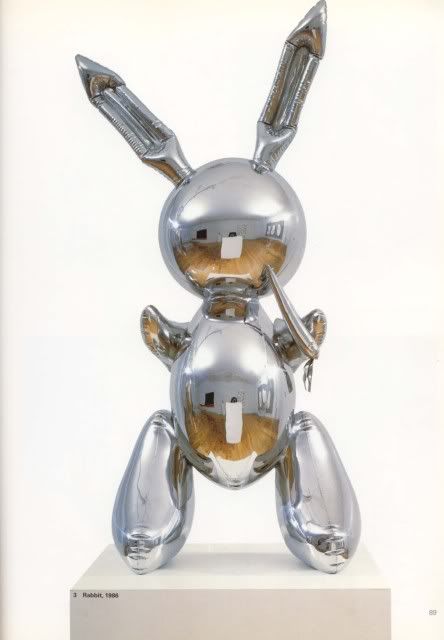

Or Jeff Koons cast-in-chrome balloons whose change in materials makes your brain twitch in strange ways.

Or the ways in which cheese becomes super processed into hundreds of different forms.

Or the genetic manipulation of grass to increase its performance as a sports surface

Or the million ways fake wood has been applied to forms that would be impossible to make out of wood.

Or how MDF is originally comes from a tree, is turned into sawdust, and then reconstituted back into a material that performs like a wood but with a generic evenness that natural wood doesn’t have.

So, to return to Ruskin, we might remake his phrase in other ways: "Nothing can be true which is not beautiful". Or "Not true is also beautiful". Or even "Nothing can be beautiful".

Before We Begin