The industrial revolution fundamentally re-shaped the organisation and mechanisms of society. Karl Marx describes for example that the division of labour creates what he calls 'alienation'

Equally, we see a kind of alienation from materials themselves.

This is expressed by John Ruskin – who if Nikolaus Pevsner is to be believed - is the origin of the morality of Modernism.

Here are a few Ruskin quotes to give you a flavour of his attitude:

"Every increased possession loads us with new weariness."

"There is scarcely anything in the world that some man cannot make a little worse, and sell a little more cheaply. The person who buys on price alone is this man's lawful prey."

"It is his restraint that is honorable to a person, not their liberty."

"It is far more difficult to be simple than to be complicated; far more difficult to sacrifice skill and easy execution in the proper place, than to expand both indiscriminately."

"He who can take no great interest in what is small will take false interest in what is great."

And especially relevant to us:

"Nothing can be beautiful which is not true."

Ruskin was describing a form of alienation from what me might call a 'natural' state caused by industrialization.

For Modernism, the idea of 'truth to materials' was fundamental - that any material should be used where it is most appropriate and its nature should not be hidden. Concrete, therefore, should not be painted and the means of its construction should be celebrated.

But honesty is hard, and if you look closely, you find that much of the 'truth' of Modernism was actually a clever disguise. That Mies' I-sections are applied decoration rather than structural. That the Villa Savoye is rendered brick, rather than concrete.

We might speculate that this demonstrates the impossibility of a singular truth – that it is impossible to manifest (especially in architecture, where costs, project managers, clients and contractors will conspire against such embedded ideology). Instead, what is important is the idea of a truth. And that you might have to lie to make your truth real. And of course, that there are many truths. Each of these truths reflects a particular position, particular view, and particular ideology.

For us, at the other end of the industrial revolution, materials have become something else. And so has 'truth'.

We might look to more contemporary sources to understand our relationship – and to chart our alienation – from materials.

We might think of Warhol's Brillo Boxes, which are representations of cardboard boxes.

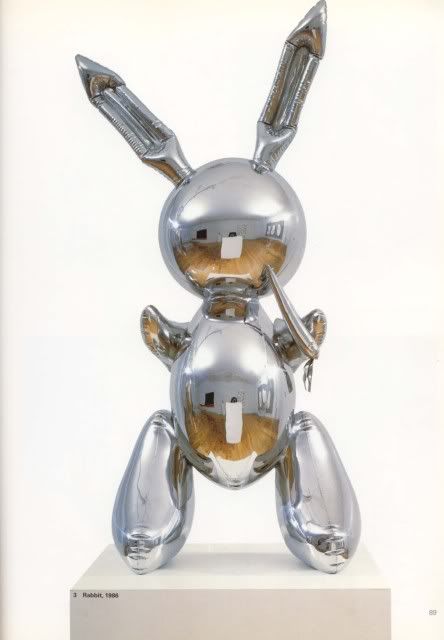

Or Jeff Koons cast-in-chrome balloons whose change in materials makes your brain twitch in strange ways.

Or the ways in which cheese becomes super processed into hundreds of different forms.

Or the genetic manipulation of grass to increase its performance as a sports surface

Or the million ways fake wood has been applied to forms that would be impossible to make out of wood.

Or how MDF is originally comes from a tree, is turned into sawdust, and then reconstituted back into a material that performs like a wood but with a generic evenness that natural wood doesn’t have.

So, to return to Ruskin, we might remake his phrase in other ways: "Nothing can be true which is not beautiful". Or "Not true is also beautiful". Or even "Nothing can be beautiful".

No comments:

Post a Comment